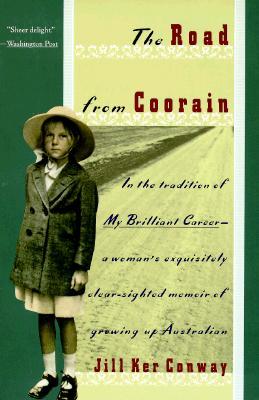

I usually keep reviews here as to the point as possible, but this book is so rich and rewarding, it deserves more. The Road From Coorain is the coming of age story of Jill Ker, a child whose whole world was an isolated farm in western NSW in the 1940s. She grew up confident in her family and her environment, and was able to negotiate her work around the farm to the extent that at eight years old she could ride for miles to herd hundreds of sheep on her own. When she first met another little girl, she didn’t really know how to socialise with her.

I usually keep reviews here as to the point as possible, but this book is so rich and rewarding, it deserves more. The Road From Coorain is the coming of age story of Jill Ker, a child whose whole world was an isolated farm in western NSW in the 1940s. She grew up confident in her family and her environment, and was able to negotiate her work around the farm to the extent that at eight years old she could ride for miles to herd hundreds of sheep on her own. When she first met another little girl, she didn’t really know how to socialise with her.

When the death of her father thrust the family into life in suburban Sydney during WWII, she underwent many cultural shocks. Jill met a working class people who were unashamedly Australian in accent and manners, as opposed to the British patterns of behaviour and attitude she had grown up with, and she began to see that there were other perspectives on life.

The wonder of this book is not only the beautiful prose and the wise steadiness of the voice, but the growing awareness of the narrator and her willingness to see a more rounded view of the world.

Jill soon learns she has to ‘manage’ her strong-willed mother and she takes refuge in her discovery of the pleasure of learning at her new school, a private Church of England establishment for girls. Here she already begins to observe the short comings of some of the teachers and the strengths of some of the others who, she notes, must have been frustrated spending their robust intellect on merely teaching young girls when they could have done so much more with their minds.

Over her time in school and university, Jill has revelation after revelation about how society treated women and Australia’s conservative culture limited growth and imagination, and stunted original academic endeavour. The revelations are shocking enough for Jill, but for a modern (Australian) reader seventy years on, it is even more shocking to realise some of these limitations and attitudes still exist, albeit more subtly.

Jill learns about life by reading, and two of the books that educate her about her controlling relationship with her mother are Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, and Carl Jung’s writings on the mother. Eventually Jill investigates Australian literature, although there is little encouragement to do so, as anything valid is only produced overseas. She witnesses the play Summer of the Seventeenth Doll and her heart opens with wonder to see the Australian experience rendered universal with characters as large as those from a Greek epic. She leaves the theatre with new feelings of pride and possibility that Australian life, too, was worthy of artistic interpretation and analysis. She notes that seeing this play ‘helped to undo a lifetime of lessons in geography’. Given that Australia has always invested millions in winning gold medals and international trophies, it was gratifying to read about Jill’s corroboration that the stories we tell ourselves are the most powerful way to communicate and build a culture and its values. Likewise, ignoring those stories in favour of some other perceived superior option, communicate its lack of value.

Jill proves herself an academic star at university, but her achievements create conflict with how she is expected to conduct herself. She and another are contenders for the university medal and they and the next in line go to Canberra to interview for jobs with the Department of Foreign Affairs. The men are employed and Jill is not. She finds out later it is because she is ‘too good looking’, ‘too intellectually aggressive’ (something she knows she has in common with her two friends), and also that ‘she’d be married within a year.’ It is also around this time she takes on a man friend who, while enjoying the stimulating company of someone intelligent, does not respect her need to work taking priority over him.

Jill is at a loss in a world where she perceives merit is of no use for getting along in life. She takes time off to go to Europe with her mother thinking she will find the answers in the academia of England. There she is even further disillusioned when she witnesses the rudeness towards women in professional life and the constant active undermining of their intellect. She goes back to Sydney University to focus on her academic career.

Jill’s final revelation comes in the form of a visiting American mining speculator. Their 16-month affair teaches her that it is possible to be loved for all aspects of her character including her mind and to be with a man who encourages her to reach her full potential. It is a short step from here to her application to study at Harvard.

This is an ultimately uplifting and triumphant story of how one person slowly becomes aware of the world around her and learns to deal with it, but also how not to give up when she realises that world does not approve of how she needs to live. To see Jill lift herself above the nay-sayers and fly off at the end is a happy ending, but what of the 1950s Australian culture that she has left behind?

Training as an historian, Jill learns how Australian history had been written to date through the lenses of politics and settlement, not through the eyes of individuals so much, and certainly not from the perspectives of minor players who lived it, which included women; how Australian life has been shaped by colonialism and the bureaucratic layers of British government.

It isn’t difficult to see the remnants of what Jill describes in today’s Australia; certainly the legacy of it. While our history is increasingly told through personal stories and women now get to retell some stories from their own perspectives (Fellow academics told Clare Wright she was wasting her time writing about the Eureka stockade as there was nothing left to say. Her book, The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, tells a story heretofore untold from the female perspective), the limited bureaucratic mindset has in large part simply shifted from British thinking to US thinking. The same old cultural cringe is still there when you scrape back that thin skin.

Jill’s story for me, put an anchor in time in the fifties, and said here, after WWII, Australia changed dramatically. But as you read her examples seventy years later, you are left wondering if much of the change has been superficial or whether those strong undercurrents from the fifties are still there stunting progress?

This book is a delight as a story without taking in all the social and political contexts, the prose flows comfortingly and the narrator good company to keep. My only nit-pick, and it jarred me out of the story several times, was the realisation that Conway has been living in the US for the majority of her life now, and it seem has long forgotten some things. Her use of the words ‘cookie’ and ‘gasoline’, and her US spelling of the proper name for Sydney Harbour as ‘Harbor’ were jarring, not least because, as she tells us, her upbringing was very British and correct, so these words would have had no place in her then-vocabulary, in fact the word ‘cookie’ has only come into regular use here in the last ten to twenty years and ‘gasoline’, still not. But good editing should have picked this up; it was first published in Britain after all.

This is an uplifting story of passion, strength, intelligence and quiet courage and should continue to be read by future generations of girls and women who have lost touch with how far we have come in our fight for equality and how strong yesterday’s women had to be to ensure change.

Comments

Total Comments : ( ) You have to register to post a comment.

RECENT COMMENTS